Some experts argue that multilateralism is under significant strain, if not altogether broken, as great power competition has re-emerged as a defining feature of global politics. The resurgence of geopolitical rivalries, particularly between the United States and China, seems to be hampering consensus-building within traditional multilateral institutions, such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization, among others. Additionally, differing from the end of the Cold War, we see that supply chains are being restructured under a plurilateral and more restricted tendency. This fragmentation of trade alliances is securitizing the products we consume daily, and thus hindering multilateralism as a force for economic cooperation. This has only been accentuated with Trump’s arrival in the White House and his expansive lay-offs to USAID professionals, which might spill over to other organizations for international development.

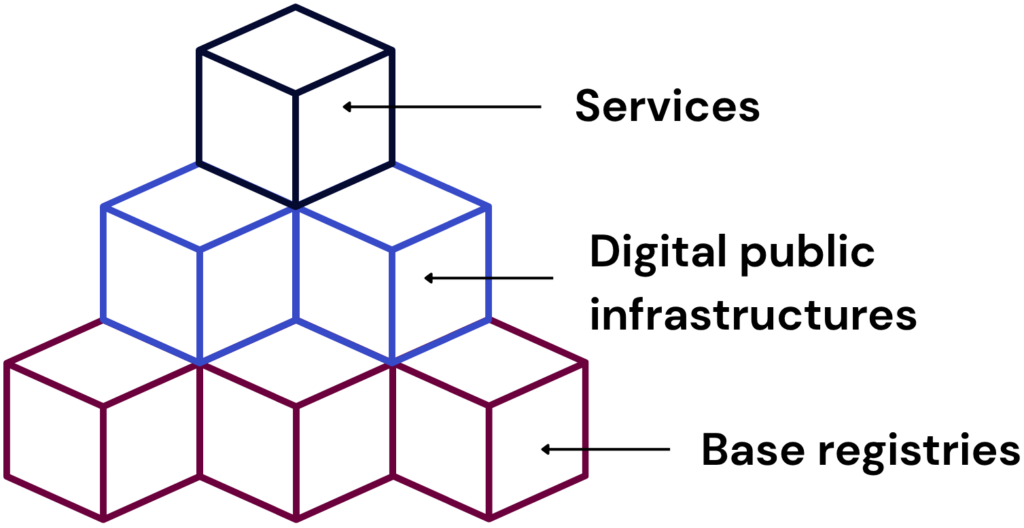

Nevertheless, some “hot” topics are still being led and dynamized at the multilateral level: one of them is Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI). In technical terms, DPIs are the physical network between the technology structure (broadband, devices, data centers, cloud) and the services provided (See Figure 1 below). Digital ID, payments, and data exchange systems are the three prominent types of DPI that are both recognized and established as examples in real-world applications for public policy.

However, DPI is also seen as an approach with a set of values that prioritizes “publicness, not a mere enabler for digital services.

Although there is a broad consensus regarding the benefits that digital common goods and applications can have in society, the over-encompassing definition of what constitutes a DPI has made it hard for some discussions to prosper and advance at the decision-making stage, especially on what constitutes “public.” Which values govern DPI’s “publicness” will be at the core of future discussions at the multilateral level, not so much on the technical side.

DPI was recognized as a term in multilateralism in August 2023, as a result of the G20 Digital Economy Working Group under India’s presidency. Such a statement underscored DPI’s importance in promoting inclusive economic growth and advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The definition that derived from the diplomatic efforts ended up being “a set of shared digital systems that are secure and interoperable, built on open technologies, to deliver equitable access to public and/or private services at a societal scale.” As part of India’s G20 Presidency, the UNDP released The DPI Approach: A Playbook about DPI in August 2023, explaining a step-by-step guide on transitioning from conventional digital public services to the building of inclusive and rights-based digital ecosystems. It is perhaps the first policy paper addressing DPI as a framework for multilateralism, and how countries, especially low and middle-income countries (LMICs), can leverage DPI. Moreover, the Playbook states which principles countries should abide by and incorporate: inclusivity, human rights, collaboration, and sustainability, among others. It takes up space to define DPI as an approach, characterized by open, interoperable technology, robust governance, and resilient local ecosystems.

The OECD’s paper “Digital Public Infrastructure for Digital Governments” was released in December 2024. The OECD defines DPI as “shared digital systems that are secure and interoperable and that can support the inclusive delivery of and access to public and private services across society,” building on the previous definition by the G20 and the UNDP. However, the terminology of what constitutes a DPI is still vague and fluid, in an attempt to adapt to every country’s context. While the paper acknowledges public-private partnerships (PPPs) as fundamental “to ensure innovation, scalability, security, and accessibility when designing, developing and governing DPI,” the OECD takes a specific look at the role governments have in designing, developing, and managing DPI, as well as the governance challenges, such as funding, public-private collaboration, and robust safeguards, including for privacy and security. The recommendations follow a lot of the rationale behind the UNDP’s Playbook. Concretely, India, although not being from an OECD country, receives a shoutout thanks to its IndiaStack as a successful case in the adoption of strategic frameworks for governing DPI.

Figure 1. Digital public infrastructure as a service enabler

In 2025, the World Bank released its white paper Digital Public Infrastructure and Development: A World Bank Group Approach, exploring the function of foundational DPI systems, sectoral applications, and the wider digital ecosystem. The paper aims to be a framework for policy-makers, introducing DPI as a strategic approach that fosters interoperability, breaks silos, and enhances service delivery, not just technology. The intention behind such paper was to bring back the topic of DPI to the broader level of multilateralism, just like the UNDP did in 2023. This is relevant because it focuses on the effects DPI should have, and not necessarily the technical deployment of such DPI. The World Bank specifically brings back the need to shift from separated silos to interoperable building blocks in digital services, a critical aspect that makes DPI a substantial different approach than standard digital public services.

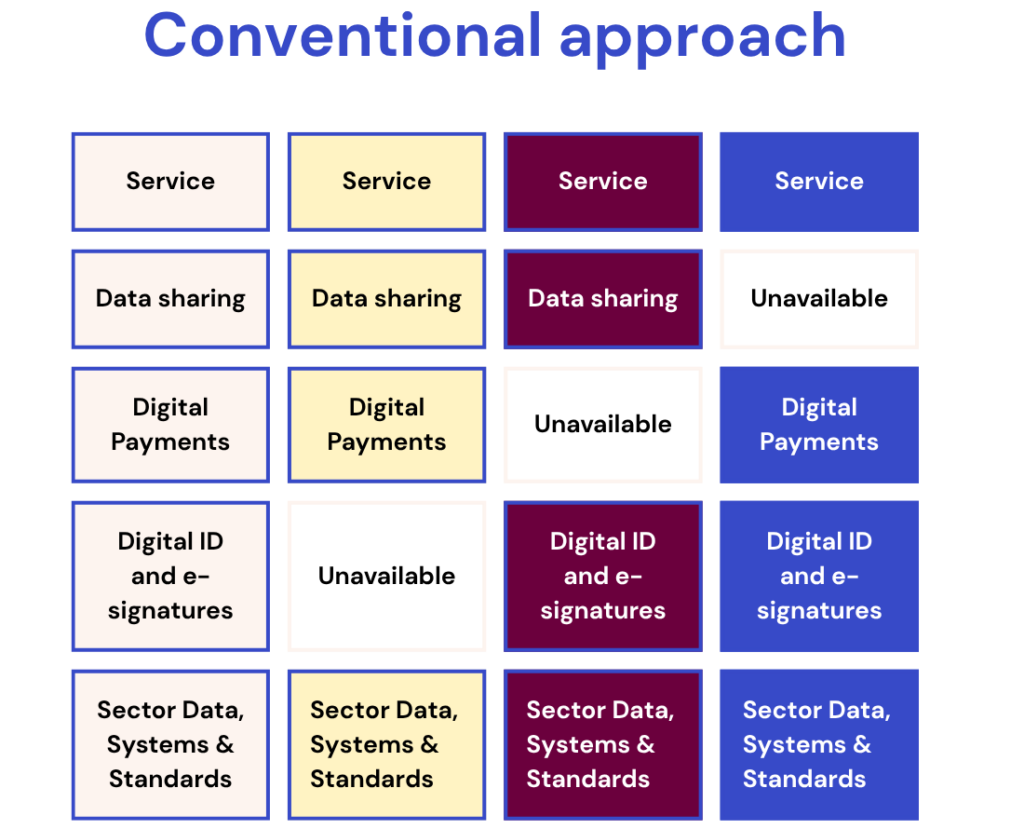

Figure 2 : DPI versus a conventional approach to digitalization

Looking at most perspectives in the multilateral space, there seems to be a union of the different perspectives that make DPI “public” and not just a mere digital infrastructure. As Professor Mazzucato explains when analyzing the “publicness” in DPI, this public approach can be understood as attributes, such as the need for interoperability, the reusing of building blocks, or open-source licenses. Such attributes enable normative values like dynamic efficiency and scale, fundamental to deploying DPI. On the other hand, DPI can also be understood as functions: community-building, upskilling, enabling a better quality of life, and economic efficiency. All of these functions intersect at the protection of human rights, and social and economic value for societies.

What is interesting in most multilateral efforts is the shared intention to bridge both attributes and functions, focusing on the way DPI is deployed but also on its overall societal effects. Technical openness, like interoperability and open-source models, is crucial. However, technical aspects are not sufficient on their own, as an intentional policy design and institutional governance that puts public value at the core is crucial in shaping equitable economic growth and social progress. For example, the World Bank explores in its new paper the positive impact of shifting from the siloed tendency of much (government) IT to interoperable building blocks, fostering efficiency when it comes to sharing information but also enabling societal values embedded in such a shift (See Figure 2). This is important because it bridges the gap that can exist between the what and the how, a necessary and tangible symbiosis that decision-makers need to see.

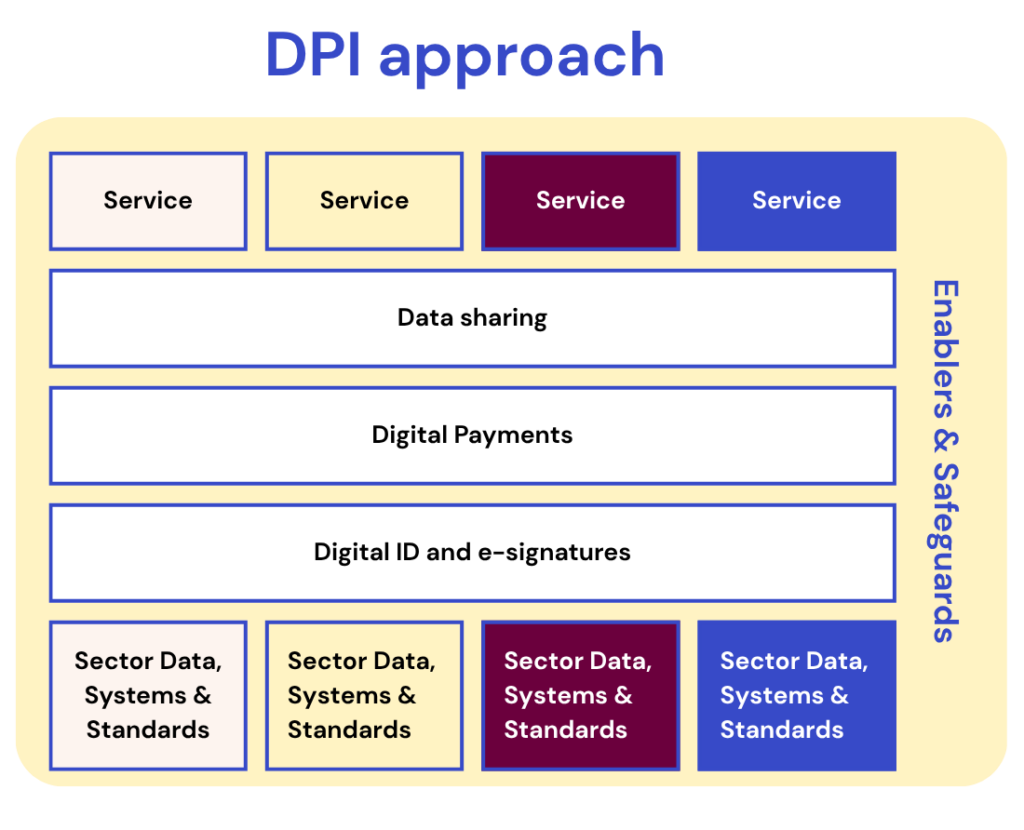

Figure 3: Example digital systems by sector

Due to the wide definition of what constitutes a DPI, and due to its many functions for societal welfare (See Figure 3), there is a lack of consensus on the public side of the question, rather than the digital one. A critical debate for upcoming debates in multilateral policy-making should be whether public ownership is the best way to contribute to public interest. As this is not desirable for many countries, democracies should take a closer look at alternatives that balance efficiency with public value when deploying their DPI. As the OECD points out, PPPs are a way forward for DPI; however, are they? And how do the rest of the countries at the multilateral level see the emergence of PPPs when it comes to DPI?

While the asymmetry in technology stack between private and public sectors may make it inevitable for PPPs to have an important role in DPI, perhaps policy-makers should discuss regulatory frameworks for private firms to be held accountable in their operations. Instead of focusing on digital ownership, the question in multilateral organizations should rather be how different public sectors with different regulatory frameworks can oversee the development of ethical private sector involvement without compromising the “publicness” of DPI. And, more importantly, how multilateral institutions can help these countries navigate these challenges, share best practices, and contribute to common strategies.

Due to a clear lack of public oversight, as Marietje Schaake explains in her book The Tech Coup, the obvious lack of technology stack from the public sector compared to the private one raises important governance concerns that should be at the center of future DPI discussions. This has become a concern for European policy-makers, as 80% of digital infrastructure is imported from the United States’ private firms. As Mazzucato explains in the paper, public values and the degree of public ownership are something that should be talked about in specifics: what are the challenges that governments may face in owning the DPI deployment? Which should be the guardrails for Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)? What risks do countries with subnational or decentralized levels of government face in governing DPI compared to the others?

Consequently, moving from the private to the public sector, the assumption that the government will make good use of this data could still be a biased axiom in many countries. The same DPI case with the same level of technological stack can perfectly diverge depending on the normative and governance aspects of the country that deploys such DPI. For example, Estonia’s X-Road system is built on principles of transparency, citizen trust, and decentralized data management, enabling secure and interoperable services while prioritizing privacy through cryptographic security guardrails and stringent access controls. The country’s strong regulatory oversight and democratic accountability have played a crucial role in ensuring that DPI enhances governance without infringing on individual freedoms, and has been used in countries like Cambodia, Brazil, Finland, and Namibia.

On the other hand, India’s Aadhaar is the country’s landmark of DPI running a vast biometric identity system. Although it has had a positive impact in expanding financial inclusion and social welfare access, concerns over data security, particularly the use of biometric data, have raised alarms among technology policy experts and human rights activists. Additionally, the misuse of personal information has reportedly excluded an important part of the population, particularly in the most marginalized communities. These contrasting examples force us to go back to the main question: the “publicness” of DPI is governed by its values. Aadhaar’s challenges show that the same foundational DPI concepts can yield different societal effects depending on governance structures, regulatory oversight, and adherence to public interest values. In countries where institutional safeguards do not guarantee public value, DPI systems can inadvertently deepen inequalities and go against such public value.

Another challenge that the DPI approach is facing at the multilateral level is the new wave of “digital sovereignty,” especially at the EU level, which has been a strong partner in multilateralism for many Global South countries. The term “digital sovereignty” has emerged as an approach to governing the technology stack for the public interest, related to the ability for countries to have control over their own people’s digital presence, referring to the data, hardware, and/or software that we use daily. The debate around DPI in the EU seems to be about privacy and data protection, driven by the belief that governments should regain control over critical parts of the technology supply chain, which are currently dominated by U.S. corporations.

However, this push for digital sovereignty could potentially endanger the core notion of “publicness,” especially when it comes to multilateral cooperation. By pursuing and limiting its partnerships, the EU risks furthering geopolitical blocs and fragmenting digital ecosystems. Examples like the EuroStack, while having clear benefits for Europe, could create artificial frontiers by only limiting partnerships with countries like the UK or Switzerland. These artificial frontiers could potentially disincentivize Europe’s digital leverage at the multilateral level, and close the door to win-win solutions with countries with experience in DPI, like Brazil. This comes at a time when the EU is investing in its Global Gateway initiative to enhance global digital investments. An overly rigid push for digital sovereignty could inadvertently undermine the effectiveness of these efforts in the Global South, limiting collaborative potential with new partners and interoperability across borders.

Despite the structural challenges that great power competition has on multilateral governance, Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) has emerged as a promising framework for collaboration. While technical openness and interoperability are fundamental, the real debate lies in the “publicness” of its values, and whether public institutions can guarantee public interest to lead and oversee DPI’s development to serve the common good effectively, with or without public ownership. While multilateral efforts effectively bridge the attributes and the functions of DPI, future discussions should revolve around key considerations such as public ownership, policy safeguards, and international cooperation to ensure DPI fosters equity, efficiency, and human rights. This is especially needed in a context where legitimate efforts in favor of digital sovereignty can hinder multilateral governance in DPI and fragment digital spaces. An effective and fair path forward will require policymakers to ponder technological innovations with an explicit set of governance structures that prioritize public value.

Senior Expert

Pau Alvarez-Aragones

Pau is a professional in international affairs with expertise in emerging technologies, international governance, and business and trade topics, particularly semiconductors and artificial intelligence (AI). He holds a Joint MA in Transatlantic Affairs from the College of Europe and The Fletcher School at Tufts University, where he was awarded the Jan Olaf Hausotter Memorial Prize for the Best Thesis in Transatlantic Affairs.

Leave a Reply